My course on the New Testament Apocrypha focused this week on part one of a two-part discussion of “Ministry Gospels”—i.e., texts focusing on Jesus’ adult life, between the infancy gospels and the passion narratives. For this first part we looked at agrapha and fragmentary texts, the latter group including Jewish-Christian gospels, several papyri from Oxyrhynchus, and the Secret Gospel of Mark. Our next class is dedicated to complete Ministry Gospels, namely the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of Philip, and two fragmentary texts we ran out of time to cover: the Gospel of Peter, and the Gospel of the Savior.

We began with agrapha, the “unwritten” sayings of Jesus, though clearly they are written or we wouldn’t have them to study. More accurately, the term denotes sayings of Jesus that are not in the New Testament Gospels, appearing as variants in Gospel manuscripts, Acts, fragmentary apocryphal texts, works of the Apostolic Fathers, in Islamic texts (go HERE for a selection of some of these), and such unlikely locations as a mosque in India, which bears the inscription “Jesus, on whom be peace, said: ‘The world is a bridge. Go over it—do not settle on it!’” I discussed the methodology scholars of the agrapha use to reduce the great number of agrapha (270 by one count) to a manageable amount of “authentic” Jesus material (though I cautioned that this is not necessarily the goal of the study of this material; there are reasons enough to study any and all of the agrapha for various goals). One student asked about eliminating agrapha that reflect anti-Christian polemic and I promised to provide an example, but I don’t seem to have anything on hand. But sayings of Jesus in the Toledot Yeshu, the Talmud, or the Gospel of Barnabas would certainly be dismissed as anti-Christian. I noted also in our discussion how agrapha blur the line between canonical and noncanonical traditions—how can a saying be “apocryphal” if it is found in a New Testament manuscript? or in a work by an orthodox writer?

I finished our discussion of agrapha with the story of Paul Coleman-Norton’s “amusing agraphon.” He claimed to have found a leaf of text in Greek sandwiched between pages of an old Arabic book in a mosque in North Africa, where he was stationed in 1943. The text was an expansion of Matthew 24:51, where Jesus mentions hypocrites being consigned to a place of weeping and gnashing of teeth. The expanded text reads, “And behold, a certain one of his disciples standing by said unto him: ‘Rabbi (which is to say, being interpreted, Master), how can these things be if they be toothless?’ And Jesus answered and said: ‘O thou of little faith, trouble not thyself; if haply they will be lacking any, teeth will be provided.’” Coleman-Norton’s text was published in Catholic Biblical Quarterly in 1950; 20 years later one of his former students, Bruce Metzger, declared the text a hoax because he remembers Coleman-Norton joking with his students prior to 1943 about Jesus saying to his disciples that the damned who are toothless will receive a set of dentures so that in Hell they may weep and gnash their teeth.

We turned next to Jewish Christian gospels, which are preserved only in quotations by early church writers, particularly Clement of Alexandria and Origen. There is much confusion in the literature about the content and identification of these texts. Where there two or three or more? Most curious to me are the variants in some manuscripts of the Gospel of Matthew from “to Ioudakion”—said to be based on an old gospel manuscript once kept in the basilica on Mount Zion in Jerusalem dated to 370-500.

We finished the first half of the class with a detailed look at Secret Mark. I began with a video of Morton Smith describing his discovery (taken from Channel 4’s Jesus the Evidence) and followed this up with an interview with Lee Strobel, author of The Case for Christ and several sequels. For his latest book The Case for the Real Jesus, Strobel interviewed Craig Evans on Secret Mark, and Evans essentially repeated the case for forgery/hoax advanced by Stephen Carlson. I listed off Carlson’s evidence myself (with a brief mention of Peter Jeffrey’s perceived euphemisms) and then countered it with arguments against his claims advanced by Allan Pantuck, Scott Brown, and Roger Viklund. I was asked what my position was; I am fully convinced by Allan Pantuck that Smith did not forge the text but I remain agnostic about whether Clement’s letter describing the text is truly ancient, or even truly by Clement. I hope, at least, that the students see that the apparent homoerotic content in the text is largely in the imaginations of its critics.

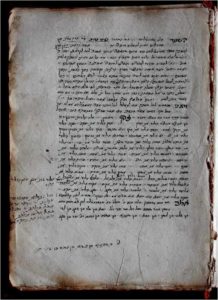

The final hour of the class was dedicated to a discussion on the major assignment for the course. Instead of having the students write an essay on an assigned text (as I have done in previous years), I decided to direct their efforts into the creation of entries for e-Clavis: Christian Apocrypha. This allows them to contribute to a project that other students and scholars will use, hopefully, for many years to come. The assignment will entail close collaboration with me, guiding them through resources such as the claves (CANT, BHG, and others) and online resources such as Pinakes. But in the end, we will have over 20 new entries for e-Clavis as well as a number of manuscript pages for Manuscripta apocryphorum. Now how do I get them to work on my next book?